Join War on the Rocks and gain access to content trusted by policymakers, military leaders, and strategic thinkers worldwide.

Criminals are nothing if not flexible. As the United States considers how to grapple with the challenges stemming from illegal and unreported fishing, our research has shown that progress made in tamping down illegal fishing may lead to an increase in piracy. As the United States focuses more on illegal fishing — particularly given China’s use of maritime militias for this act — it is important to understand how support for policing may inadvertently spawn other illegal acts that impinge on U.S. global interests.

Just days before leaving office, the Trump administration declassified its “Strategic Framework for the Indo-Pacific” region. The Trump administration’s approach focused primarily on great power competition with China. The Trump administration acknowledged the problems of maritime security, including piracy and illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing, and the need to build cooperative relationships with Indo-Pacific countries and assist them with capacity-building.

In practice, however, the Trump administration never really made maritime security a strategic priority. The Biden administration has refocused U.S. government attention toward Asia, seeking to reengage with Pacific allies (e.g., the Quad partnership renewal, the trilateral submarine deal with the United Kingdom and Australia, and modernized bilateral alliances), sometimes at the expense of European partners. While the recent Pacific Deterrence Initiative, an effort to better prepare U.S. forces for armed conflict in the Indo-Pacific region, centers on China’s military modernization, the program also shores up cooperative security partnerships in the region as well as enhancing maritime awareness.

To tackle maritime security comprehensively, however, China should not be the sole focus of U.S. policy in the region. The United States should recognize that nontraditional maritime security threats remain significant barriers to a free, safe, and prosperous maritime domain in the Indo-Pacific. As maritime piracy has declined globally, there has been an increased focus on the role illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing plays in marine ecosystem destruction as well as a gateway to other maritime criminal activity. Illegal foreign fishing has been long believed to drive sea piracy. This narrative is clear when it comes to Somali piracy in the greater Gulf of Aden. While foreign industrial trawlers can sometimes push local anglers into maritime crime, the relationship is more nuanced and localized than previously thought.

In some geographic spaces, illegal fishing is perpetrated by local actors, not foreign ones. Pirate attacks are also localized in that local actors are once again responsible for the vessel boardings. Our evidence suggests these two maritime crimes are related. Where illegal fishing declines, piracy tends to rise. Presumably, local anglers fish both legally and illegally in the same waters. If illegal fishing is removed as an option for increased income, vessel robbery is sometimes used as a replacement for that lost revenue. For policymakers, our study cautions that local efforts to combat illegal fishing can inadvertently shift criminal activity to ship raiding. Sustainable policy approaches that address the underlying causes of maritime crime clearly remain critical. But, in isolation, they are insufficient since perpetrators can easily shift from one illicit activity to another. Comprehensive policy actions, such as the Indo-Pacific Partnership for Maritime Domain Awareness, the new High Seas Treaty, and the Port States Measures Agreement will help address both the grievances driving criminal activity as well as the coordinated regional actions necessary to prevent displacement.

Illegal Foreign Fishing Is a Problem, but It’s Not the Primary Cause of Local Maritime Crime

Our research, funded through the Minerva Initiative, explores a critical element of maritime insecurity in the Indo-Pacific. Healthy, sustainable marine fisheries are essential to the well-being of thousands of communities worldwide. Fishing supports millions of jobs and provides even more people with their primary source of protein. Protecting this resource can help improve maritime security. One principal narrative on sea piracy maintains that illegal foreign fishing drives local anglers to maritime crime. Based mostly on the Somali experience, this narrative centers on both overfishing and the extensive damage inflicted on marine ecosystems by industrial foreign trawlers in Somali waters.

The Somali author Awet Weldemichael insists that “Somalia’s commercially oriented, small-scale, artisanal fishing became one of the main casualties of the intensification of foreign [illegal, unreported, and unregulated] fishing.” The near-complete absence of centralized authority in Somalia after the collapse of the Siad Barre regime in 1991 precluded the supervision of Somali waters, with the consequence that local fishers sometimes took their boat-handling skills to maritime crime. This story became a popular framework to explain the onset of piracy in other parts of the world, such as in the Gulf of Guinea. However, while it sounds plausible at first glance, a more in-depth analysis cautions against such a “causal leap.” There is little doubt that large-scale illegal fishing by industrial trawlers tends to deplete marine resources, sometimes driving local fishers out of work. However, it remains unclear whether illegal foreign fishing is a primary trigger for pirate attacks against commercial cargo vessels. Quite the contrary, this narrative only provides a justification and legitimacy for the pirates.

The Local Story Needs to Be Understood to Better Address Illegal Fishing

Past studies show that there are multiple interconnected causes of maritime piracy. Piracy thrives in places where the maritime borders between countries are disputed and where littoral governments lack the ability or will to stop it. It also exists where international cooperation falters and where the local fishing economy declines.

Surprisingly, piracy does not appear to be concentrated in areas where governing institutions have collapsed. Indeed, pirates need ships to prey on, operational commercial ports where goods are exchanged, and the ability to sell stolen loot through illegal markets. Previous research establishes that piracy regularly thrives in and around ports and anchorages where local governance is both weak and corrupt. Illegal fishing also prospers in the waters of countries characterized by fragile political institutions that create opportunities for collusion between criminal actors and state authorities.

Our research explores the link between illegal fishing and piracy. We observe that sea piracy incidents follow declines in illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing, and we infer that local anglers are substituting one illicit activity for the other.

Past works on the crime milieu indicate that factors like an individual’s criminal history and networks are essential in predicting such incidents. Past works have also noted that pirates are sometimes fishers since they have the boat-handling skills to navigate the waters. We argue that constraints on illegal fishing, due to either enhanced policy measures or depleting resources, lead local perpetrators to engage in risky but more rewarding pirate attacks. We also propose that opportunistic pirate attacks involving local fishers are common in target-rich, high-shipping-traffic areas. Since the perpetrators are from the local area, we should be able to observe a decrease in illegal fishing followed by an increase in piracy incidents.

For evidence, we initially focus on Indonesian waters between the years 1990 and 2017. We systematically analyze available data on illegal fishing and piracy incidents. We first carve up the entire Indonesian exclusive economic zone into 55-by-55-kilometer grid cells and comb through the data in each grid cell to explore this association. The results obtained from these analyses are robust, and they support our causal narrative.

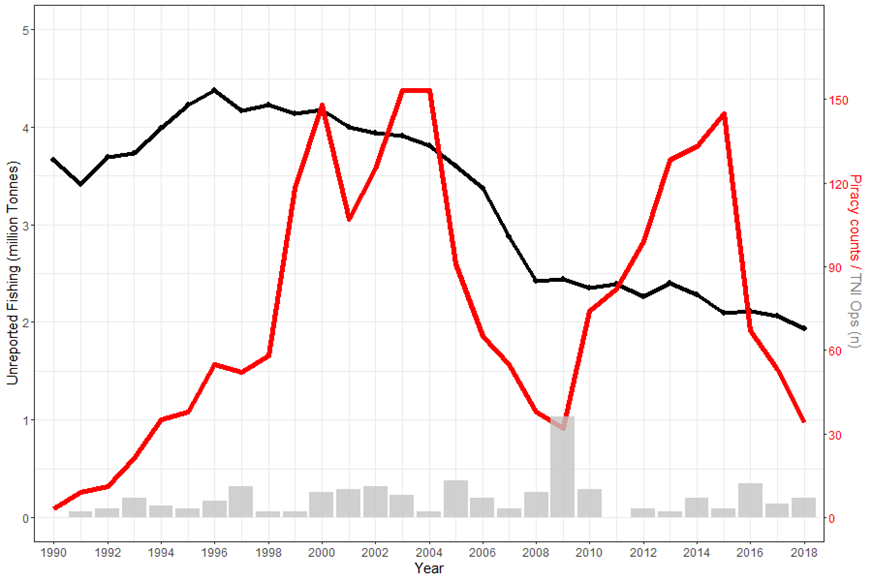

As shown in the figure below, illegal fishing in Indonesia has generally declined since the 1990s, largely due to better enforcement, but pirate attacks have increased and decreased significantly at different times depending on macro-economic and political factors.

Pirate attacks require targets. We accounted for targets by including the yearly vessel traffic density from the Automatic Identification System data. As shown in the figure below, vessel traffic is not uniform across the Indonesian maritime space.

Our primary findings from the statistical models show that a decrease in illegal fishing, and nearby vessel traffic, independently increases the odds of piracy events in an area. But more importantly, the interaction of these two events nearly doubles the likelihood of sea piracy incidents in the area. We do not find a decline in legal fishing to have the same effect on piracy. We think that local efforts to combat illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing inadvertently shift criminal activity to ship raiding.

A Free and Prosperous Indo-Pacific Requires Awareness of the Blue Economy and Blue Crime

In an address outlining his foreign policy vision, President Biden said his foreign policy will have the diplomacy of Benjamin Franklin, the vision of the Marshall Plan, and the passion of Eleanor Roosevelt. In addition to defending the homeland and confronting natural adversaries, the president cited human rights, climate change, development, international law, and democracy at home and abroad as major points of focus.

Later, when the Biden administration posted its National Security Strategy, once again the Indo-Pacific took center stage, with China representing the central security challenge confronting the United States. But transnational organized crime, including illegal fishing, is also noted as a shared threat to peace and prosperity. At a recent United Nations Ocean Conference, the administration emphasized working with global partners to use the ocean to combat the climate crisis and boost the blue economy. The fishing industry is a labor-intensive sector with very few legal and social safety net protections where illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing and maritime piracy are key concerns.

Perhaps the good news is that it does seem like the U.S. government has been improving its approach to illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing. There have been federal-level attempts to focus on this issue. In 2014, the Obama administration issued a memorandum on illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing. In 2020, during the Trump administration, an interagency working group was established and offered its own recommendations, including directing the secretary of state to make combatting illegal fishing and seafood fraud a diplomatic priority. The Biden administration’s 2022 memorandum continues with a full-government approach and, in our view, correctly emphasizes human rights, development, information-sharing with our partners, and integrating combatting illegal fishing as part of our trade and diplomatic policies.

Conclusion

The Biden administration has joined with other nations to prioritize illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing through capacity investments and local governance improvements and by emphasizing human rights concerns. The U.S. Coast Guard is now at the center of maritime security and capacity-building in the Indo-Pacific. Rear Admiral Jo-Ann Burdian recently noted that U.S. Coast Guard forces stationed in Hawaii are helping to train maritime security forces in the Indo-Pacific to combat illegal fishing. Combatting illegal fishing is undoubtedly a step in the right direction, but our research highlights the importance of carefully assessing policy measures to avoid unintended consequences. While measures to combat illegal fishing can deter foreign perpetrators, there is also a potential risk of displacing crime from one type to another. In this case, local illegal fishers may turn to ship raiding. Moreover, previous research indicates that the odds of pirate attacks increase when cooperation among countries in the region is low. Consequently, a holistic policy approach that involves regional partnerships remains critical to prevent and deter crime in the maritime domain.

One example of this was in May of last year, when the United States, alongside Australia, India, and Japan, inaugurated a new initiative designed to uphold a free and open Indo-Pacific called the Indo-Pacific Partnership for Maritime Domain Awareness (IPMDA). The partnership will serve as a mechanism for cooperation on COVID-19 response and global health security, climate, critical and emerging technologies, cyber, space, and infrastructure. Criminals can be difficult to find and apprehend in the maritime domain. Tracking systems on vessels can be disabled, and many ships that engage in illicit activity operate at night to thwart government surveillance. Putting a stop to maritime crime requires both information collection and sharing. This is where the regional fusion centers can help by providing real-time data on crime patterns to local authorities to facilitate more effective patrolling of the spaces where criminals are working.

In March 2023, after ten years of negotiations, nearly 200 countries signed on to a new international framework being called “the High Seas Treaty.” The new treaty will put international waters into protected areas to limit damage from activity that is not consistent with new international conservation objectives. This could mean illegal fishing. There is a clear multilateral appetite for international cooperation on managing international waters. Our research shows that maritime threats do not occur in isolation. As illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing declines, and nearby vessel traffic increases, maritime piracy increases as well. Therefore, combating piracy must be done in combination with illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing through a multifaceted and sustained approach. Environmental protection, development, and a robust blue economy are vital. But so too is an international regime with clear, enforceable rules that provide guidance to littoral states that possess the capacity to surveil, arrest, and prosecute maritime criminals. The United States should continue to lead multilateral efforts that are designed to improve mechanisms for cooperation, capacity-building, and information-sharing.

Brandon Prins (@bcprins) is professor of political Science and Department Head at the University of Tennessee-Knoxville, USA. He is the co-author of Pirate Lands (Oxford University Press, 2021).

Anup Phayal is an assistant professor in the Department of Public and International Affairs, University of North Carolina at Wilmington, USA.

Aaron Gold is a visiting assistant professor in the Department of Politics at Sewanee: The University of the South, USA.

Curie Maharani is a Lecturer at BINUS University, Indonesia.

Deng Palomares is a Senior Scientist and Project Manager of the Sea Around Us at the University of British Columbia, Canada.

Daniel Pauly is University Killam Professor of Fisheries at the University of British Columbia, Canada.

Sayed Fauzan Riyadi is Executive Director of the Center for Southeast Asia and Border Management Studies at Raja Ali Haji Maritime University, Indonesia.

Funding for this project was provided by the U.S. Department of Defense, Office of Naval Research, through the Minerva Initiative. The opinions and interpretations are those of the authors and not the U.S. Navy or Department of Defense.

Image: U.S. Coast Guard photo by Chief Warrant Officer Sara Muir